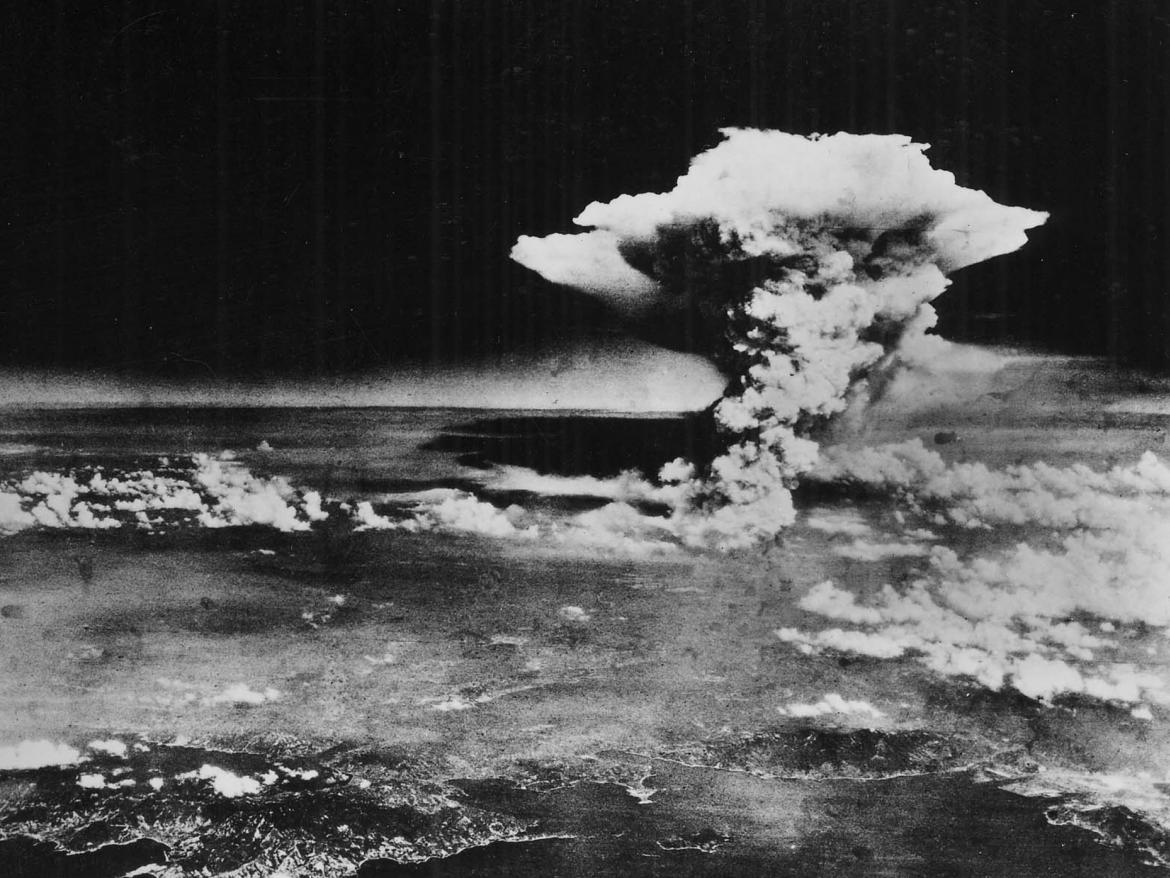

Fifty years after she survived the American nuclear attack on Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945, Sachiko Yasui recalled what happened when the bomb went off as she played with four other children in the road near her house:

There was an eerie flash of brightness that looked like an overlapping of suns, and then a violent blast assaulted us. This was followed by a droning sound, and for an instant it felt like my body was floating in the air. I couldn’t see anything at all, and in that brief period of time all five of us found ourselves buried alive.

I found myself trapped under the debris of the houses, and when I tried to breathe dirt came pouring into my nose and mouth with the force of water flowing from a hose. At the same time I heard two of the girls start to scream.

I have no idea how much time passed, but eventually I was pulled out from under the debris. By that time the fires were already moving in on us.

After they dug out the other four, we all fled to the top of the nearby mountain. Because I was crying the whole time, I have no idea where we walked or how we got to our destination. The adults carried the bodies of the other four children, for they had suffocated to death after swallowing so much dirt.

After my two older brothers passed away, I grew feverish and came down with symptoms like loss of hair, bleeding from the mouth and a complete lack of appetite. On top of that, the skin of my arms and legs broke out in some kind of rash. Along with my fever, my wounds started to fester, attracting swarms of flies that laid eggs in them, something that was excruciatingly painful. There was no medicine to put on, and without any gauze, bandages or disinfectant they grew progressively worse.

We had been thrown into the world of death and destruction, and less than a month after the atomic bombing, twenty-three of my relatives, including brothers and sisters, had died.

Ms. Yasui’s story hung over me as I read my own six-year-old daughter to sleep in our eastern U.S. home on the evening of Aug. 5, 2020, about 75 years and an hour after my country first used a nuclear weapon in war on Hiroshima.

As I watched my daughter drift off, tucked in under the innocence and security I strive to weave for her, I could not help but look down and ponder how I would feel if it were her skin covered in festering wounds, her gums bleeding not from the baby tooth she just lost but from ionizing radiation she had just been bombarded with, or her eyes welling in tears of bewildered frustration as her beloved older brother faded away before her.

It is striking, then, to reflect on the fact that, in my three-plus years leading FCNL’s lobbying on nuclear disarmament, sitting through countless congressional hearings and floor debates about how much to spend on this or that nuclear warhead or missile or bomber, I can’t recall a single time I’ve heard a member of Congress or an executive branch official talk publicly about the actual physical effects of nuclear weapons. The language used to discuss these weapons seems designed entirely to hide or minimize their awful power.

The language used to discuss these weapons seems designed entirely to hide or minimize their awful power.

Nuclear weapons are never described as enormously wide-area blast, incineration, and ionizing radiation dispersal devices. They are said to deter—or to use the more grandiose words of the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, to make “essential contributions to the deterrence of nuclear and non-nuclear aggression.” Policymakers assert that nuclear weapons provide “assurance” to allies. New nuclear warheads are described as mitigating risk. Some nuclear weapons are given the moniker “low-yield”—even when they would produce explosive blasts a thousand times more powerful than the 1995 Oklahoma City truck bombing. Nuclear weapons, to some, apparently even form the “bedrock” of America’s national security.

If one only listened to congressional discussions about nuclear weapons these days, one might never know what specific military purpose U.S. officials think the massive blast overpressures or heat or ionizing radiation generated by nuclear weapons actually serve.

What is more, if one only followed public congressional debates on nuclear weapons policy, one would think that nuclear weapons somehow manage to provide all those supposed benefits of deterrence and assurance and bedrock security seemingly without ever actually threatening to inflict much damage on anyone in particular.

Certainly at no point in listening to those congressional debates would a citizen need to be troubled by the near-certainty that another American use of nuclear weapons would mean searing some other six-year-old girl’s skin, or poisoning another older brother, or flinging storms of glass shards into a grandmother’s eyes, or sending another batch of blinded victims crawling to slake their desperate thirst from irradiated streams.

The suffering and destruction and death that two nuclear bombs wrought in Hiroshima and Nagasaki are not mere history to be noted on a day or two in August, and then moved on from. Every one of the 3,800 or so nuclear weapons the United States government retains ready to be unleashed on its citizenry’s behalf contains condensed and poised within it the beginnings of countless more stories like that of Sachiko Yasui. (And when a strong case can be made that the way nuclear weapons were used against Hiroshima and Nagasaki would be a war crime today, the facts of 75 years ago remain a relevant policy question for current weapons and plans.)

The awful stories that started on those two days in August 75 years ago continue to demand a major reconsideration of these terrible weapons.

Congress and the executive branch, and the Americans who vote for them, face substantial, even trillion dollar decisions over how to proceed with America’s nuclear weapons arsenal. It is long overdue for members of Congress to start talking plainly about what nuclear weapons do and precisely what benefits they think those terrible effects supposedly offer.

Putting the effects of nuclear weapons at the center of these policy debates would reveal that those who perpetually argue in support of this new warhead or that new delivery system and who challenge each new international agreement to constrain nuclear weapons are essentially saying that the only way to secure the innocence, freedom, and safety I seek for my children is to perpetually threaten some other parent’s child with the traumas of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

I refuse to accept such a fatalistic, depressing vision. There is simply no justification for pouring endless billions of dollars into all these proposed new nuclear weapons and delivery systems, nor for sustaining perpetually the numbers and capabilities we already have. All the awful stories that started on those two days in August 75 years ago continue to demand a major reconsideration of these terrible weapons and a major change in how we talk about them.

Surely six-year-olds past and present deserve nothing less.