The intersection of U.S. housing policies and community violence illuminates a stark reality: systemic racism has perpetuated socio-economic disparities linked to increased urban violence. Investing in violence interrupter (VI) programs is an imperative step to breaking this cycle, offering localized solutions to mitigate and strategically confront violence rooted in systemic racism.

Addressing Socio-Economic Inequities through Violence Interrupter Programs

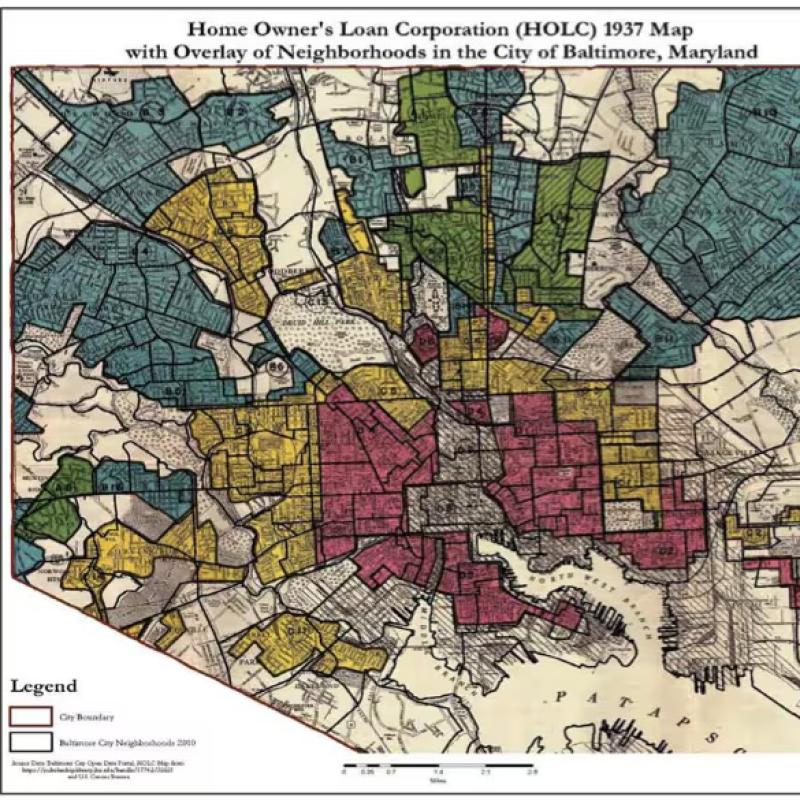

The term “redlining” stems from a 1930s practice of designating neighborhoods as “risky” or “undesirable” for investment, often based on racial demographics. This discriminatory practice, originally related to government-backed mortgages, disproportionately discouraged financial vitality in Black and Brown communities.

As a result, these areas are characterized by heightened housing instability, lower rates of homeownership, and a greater likelihood of experiencing housing cost burdens and eviction. Limited housing opportunities often led to substandard living conditions, overcrowding, and a lack of essential resources.

Simultaneously, residential segregation and discriminatory housing practices often blocked Black and Brown people from areas unaffected by redlining.

The systematic denial of homeownership through federal policies and private mortgage lending practices deprived these communities of opportunities to accumulate wealth, as owning property is a primary means of building financial stability and generational wealth. This exacerbated existing inequalities, with lasting impacts. For instance, in 2016, white families had a median family wealth of $171,000 — dramatically higher than the median wealth of $17,600 for Black families.

The Connection Between Redlining, Poverty, and Violence

Despite redlining formally ending in 1968, the consequences continue to deeply impact Black and Brown urban communities today. Urban community violence has the most devastating impact on regions marked by concentrated poverty and racial segregation.

Similarly, urban neighborhoods facing high levels of poverty, inadequate public services, limited educational opportunities, poorer health outcomes, and income and asset inequality also suffer from prevalent violence. Redlining led to underinvestment in these areas, exacerbating concentrated disadvantage, which in turn is strongly associated with increased homicide rates over time.

Addressing the Roots of Violence

Violence interrupters provide mediation, support, and resources to communities grappling with the consequences of systemic injustices, effectively addressing immediate conflict while indirectly confronting broader systemic issues, emphasizing trust-building, mediation, and rehabilitation over punitive law enforcement measures.

Violence interrupters offer hope for breaking the cycle of violence entrenched in decades of discriminatory housing policies.

In regions characterized by concentrated poverty and racial segregation, the impact of violence interrupters is particularly significant, offering hope for breaking the cycle of violence entrenched in decades of discriminatory housing policies.

While VI programs do not directly address redlining, their efforts play a crucial role in curbing violence stemming from intentional systemic racism. By targeting conflicts at the grassroots level, VI programs can disrupt the chain reaction of violence fueled by socio-economic inequities.

Case Study: Cherry Hill, Baltimore

Cherry Hill, Baltimore is historically notable as the nation’s first, largest, and likely only planned suburban-style development for African Americans. Cherry Hill illustrates the enduring legacy of redlining, as it reflects the consequences of underinvestment in urban neighborhoods, closely linked to current high rates of violence. However, things are changing, and VIs play a major role.

In 2015, Cherry Hill celebrated 400 consecutive days without a homicide, a milestone credited to initiatives like Baltimore’s Safe Streets — a VI program. The remarkable achievements of Cherry Hill in reducing violence highlight the transformative impact of violence interrupter programs and underscore the urgent need for similar initiatives in other redlined communities nationwide.

Addressing Economic Disparities to Reduce Violence

Deliberate economic disadvantages imposed by the U.S. government disproportionately affect Black communities, fueling disparities that can result in violence. We need policies that move from reactive carceral practices to proactive, community-focused violence prevention.

Funding local organizations that keep their communities safe is a vital first step. In the current U.S. budget, $50 million has been allocated for Community Violence Intervention, maintaining funding from the year before to support these crucial programs. In the next fiscal year, FCNL is urging $60 million for CVI as part of our broader efforts toward economic justice.