George Floyd should be alive today. As should Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, David McAtee, and the hundreds of other Black women and men who recently died due to police brutality and racism.

George Floyd should be alive today. As should Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, David McAtee, and the hundreds of other Black women and men who recently died due to police brutality and racism.

What we’re talking about isn’t just something I’m passionate about. It’s my reality.

Recently, I attended one of the protests in Washington D.C. As we stood peacefully outside a public park, an organizer called out the names of Black women and men who have been murdered. For more than 10 minutes, we had a call and response: Attatiana Jefferson; say her name. Eric Garner; say his name. Sandra Bland; say her name. Philando Castille; say his name. Each time the organizer paused for a breath, I thought that we were at the end of the list. The truth is, we had barely acknowledged the hundreds of lives stolen.

Six years ago, Eric Garner spoke his last words: “I can’t breathe.” George Floyd said the same. Six years later, we’re still fighting for Black people to be able to breathe and to exist in a world that has robbed us of so much.

We’re looking at 400 years of oppression. Years of mothers mourning their children’s murder. Of children wiping their mother’s tears—as Philando Castille’s girlfriend’s daughter did—while also whispering to her mother, “I don’t want you to get shooted, too.” She was only four. As a Black, Latino Quaker I live at the intersection of many identities. What we’re talking about isn’t just something I’m passionate about. It’s my reality.

From the comfort of a couch, inside of a home, nestled away from fires and pleas for justice, apathetic onlookers warn protesters to remain peaceful and to be strategic. But 400 years of peace and strategy later, we still cannot breathe.

Black people alone cannot dismantle systems that we did not create.

Racism feeds systems that keep Black and brown people oppressed. It’s easy to be apathetic or say, “Well I’m not racist, I have a Black partner, friend, colleague”. But racism has shapeshifted; it’s not just the overt slaughtering of Black people. It’s also microaggressions, like comments about natural hair and the suggestion that when a Black woman emotes, she must be angry. Racism is the assumption that having a carne asada while brown or birding while Black, is reason enough to call the cops.

Black people alone cannot dismantle systems that we did not create. Being a true ally comes in the form of using white privilege to advocate for liberation. It’s uncomfortable, but it’s necessary. To cast out racism and police brutality, it will take a multidisciplinary approach to identify and root out racism.

Maybe you’re thinking: “I’ve prayed, now what?” Or “I can’t get through to racist people in my circle. Now what?” Liberation won’t come overnight, but if our allies commit to do the work, a better tomorrow lies ahead—a tomorrow where Black men and women can breathe. I don’t have all the answers, but here are a few ideas to get started:

- Educate yourselves. Listen to Black women. Now is the time to hear what the leaders of this movement have to say.

- Attend a protest. Suit up with your mask and stand alongside your Black brothers and sisters, who have shown up despite being shot with rubber bullets, tear gassed, and threatened by our president.

- If you cannot risk exposure to COVID-19, drop off water and snacks to your local protest rest stop.

- Talk with white people in your life.

- Of course, call your member of Congress and tell them you support bold reforms to policing in the United States (fcnl.org/cjaction).

The burden is on us as believers to hold Black and brown people in the Light. To alleviate poverty for poor people. To advocate for criminal justice and police reform. And most urgently, to support oppressed people—because all lives can’t matter until Black lives do.

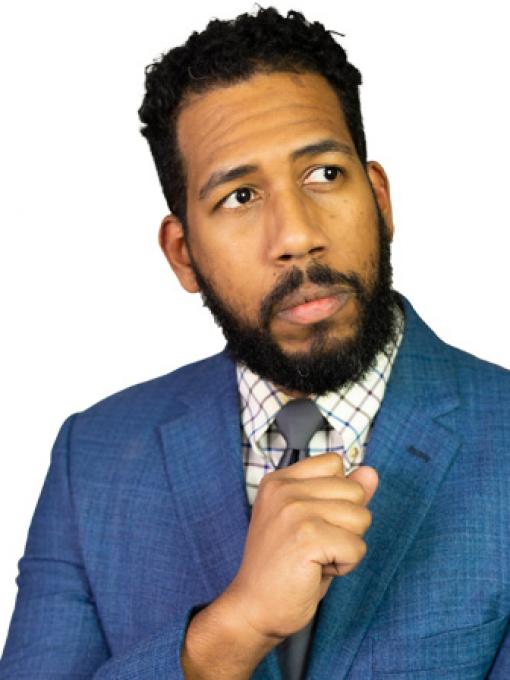

José Santos Woss is legislative manager for criminal justice and election integrity. A video of this article is at fcnl.org/twfjosewoss.